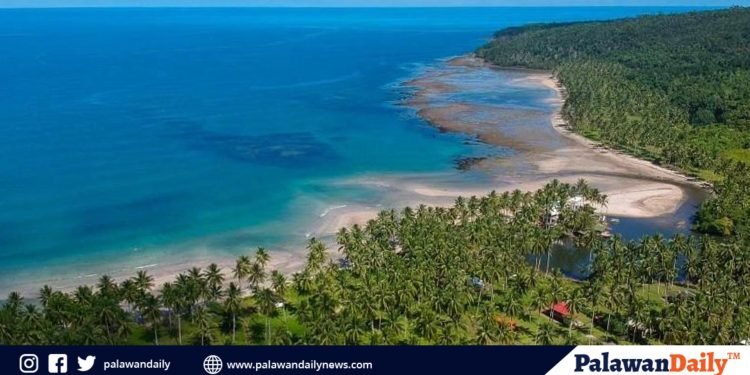

In Aporawan, in Palawan’s sleeping town of Aborlan’s west coast, where jobs are scarce, locals’ substantial dependence on fishing stuck them in a cycle of poverty as environmental and climate hazards exacerbated struggling low-income families’ hope that sooner, big businesses would operate in their village to give them daily wages to survive.

Every day, they struggle to survive, interrupted by weather disturbances such as the southwest monsoon (habagat) and other unpredictable climate conditions that they observe becoming harsher. 42-year-old farmer Reynaldo Mesias, a father of five kids and an indigenous person belonging to the Tagbanua community, said that risking lives to venture to rough seas is common to them.

Two months ago, Mesias’ neighbor in Aporawan, fisherman Joran Matuar, was found dead after their boat capsized when they ventured fishing while stormy weather prevailed.

During stormy weather and monsoons, a river near Sitio Bubusawin swelled; thus, farmers and fisherfolk in the area who were unable to work were left with no other choice but to prepare steamed cassava for their meals.

“Pag ganito ang panahon tiyaga na lang, kain ng kamoteng kahoy, kasi hindi ka pauutangin ng bigas sa tindahan kasi matagal daw sila bago mabayaran. Napakahirap pag masama ang panahon,” 48-year-old farmer Cristobal Vicente emotionally narrates.

Cristobal used to venture on sea for a living, but a near-death sea accident while fishing forced him to shift to working as a farmworker locally known as a “hurnal,” while also farming in a small land patch near a river in Aporawan. He has four kids, and two of them are in school.

His wife, 34-year-old Mary Ann, also worked as a farm worker to make both ends meet for their family. But they said that working as a jornal that gave them a P350 daily wage is only seasonal; in one month, they only worked for seven days.

“Minsan sa isang buwan, may isang buong linggo na may trabaho kami, naga-tabas, magtatanim, iba-iba basta trabaho sa bukid,” she said.

She said that the majority of the people in Aporawan village are small fishers, who own a motorboat for fishing within the municipal coastal waters, an area within 15 kilometers from the shores, or work for commercial fishers, earning meager pay only.

Despite limited economic activities in their village, Mary Ann did not lose hope, and she expected that one day, a big business establishment would operate in their place, which would provide locals with daily wages.

Cristobal said that the result of the lack of economic activities in their village is visible—joblessness, low income among locals, and poverty. But he said that what made them more helpless was the absence of basic services like healthcare and clean water. While Barangay Aporawan has a multi-purpose building they call a health center, there’s no medicine available. They tried requesting medicines from nearby Napsan village, already part of Puerto Princesa, but their staff refused, citing that their supplies are intended only for Napsan residents. He said that since the town proper of Aborlan is 107 kilometers away from their village, they may need P400 for the motorcycle for hire fare from their village to the south national highway located in Montible and another bus ride from the highway of Montible to Aborlan. That would be P800 for a back-and-forth ride.

While locals are earning meager resources on a daily basis, the prices of basic commodities in remote areas like theirs are higher. While P35-P40 per kilo (some P87-P100 if equivalent to 1 ganta) of rice is available in town proper, theirs is scarce. Thus the price is at P130 to P150 per ganta (1 ganta is equivalent to 2.5 kilos); therefore, there is a difference of roughly P16-P21 per kilo.

“Mahirap na nga kami at walang permanenteng trabaho, mas mahal pa ang mga bilihin dito sa amin, kompara dun sa binibinta sa bayan,” said Cristobal.

He admits that these things trapped them in cycles of poverty and marginalization, making them exposed to health problems, financial insecurity due to exorbitantly priced basic commodities, and other negative outcomes.

Mesias, on the other hand, an indigenous people farmer, said that he planted rice in sloping areas also known as kaingin. It is a traditional slash-and-burn farming method used for subsistence farming where land is cleared by cutting and burning vegetation to provide space for crops. He also grows vegetables, which, after harvesting, heto Bucana in Barangay Iwahig, 66 kilometers away from their place. He wanted to deliver his harvest to the city proper of Puerto Princesa, where he could get a higher price for his products, but without a driver’s license and a license for his improvised motorcycle with a sidecar, also known as a “topdown,” this constrained him from doing so.

For him, their place, where joblessness prevailed, is considered a deprived inner area, away from their town center. Aporawan is 72 kilometers from Puerto Princesa, 91 kilometers from Quezon town proper, and 107 kilometers from Aborlan town proper, or an estimated two to two and a half hours of land travel.

Based on the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), Aporawan’s population was 4,303 (2020 census) with an estimated 1,000 households with an average of 4 to 5 members per household.A study, especially the Environmentally Critical Area Network (ECAN) of the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD), a key strategy of Republic Act 7166, also known as the Strategic Environmental Plan for Palawan (SEP) Act, found that the local landscape, specifically near protected zones, impacts locals’ employment and income.

In 2023, 19.6 percent, or approximately 48,800 families, in Palawan live in poverty. There are also 8.7 percent, or 73,288 individuals, in the entire Palawan’s 23 towns who were considered food poor, or individuals who couldn’t afford basic food needs.

Some studies by locally based scientists on Aporawan’s socio-economic status corroborated with the locals’ narrative.

In a study, “Sustainability of the fishing industry in Aborlan, Palawan,” authored by Western Philippines University (WPU) Assistant Professor II Angel A. Alili Jr., it was presented that “in spite of the presence of abundant marine resources, most fishermen in the study locale live below the poverty line due to the loss of fishing grounds to big fishers, rent gear and boats at burdensome rates, or become exploited as they are forced to sell their services to commercial fishers,” citing also a study authored by a certain Magbanua.

In his study, some 34 percent of respondent small fisherfolk in several Aborlan fishing villages, including that in Aporawan, confirmed that their fish catch ranges from 10 to 15 kilos, while 26 percent claimed that their catch is more than 20 kilos, and 24 percent said that their catch is from 16 to 20 kilos. There are 187 of the 235 fishermen respondents, or 79.6 percent of them, who said that they sell their fish catch as fresh in the nearest market. This implies that they prefer to sell fish directly rather than to process it into other forms of by-products that could fetch higher value.

Without adequate interventions from the government, the social and economic conditions of the local residents in this coastline facing the West Philippine Sea will remain bleak. Some of them believe that there is a glimmer of hope when their angst, sentiments, and concerns are properly heard and documented during barangay assemblies and brought to the tables of our decision makers—especially mayors, congressmen, or governors, who promised them a better life during election campaigns.