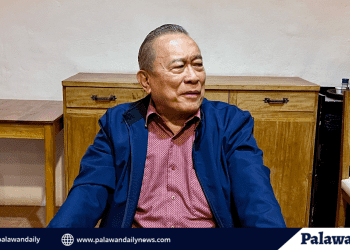

Bishop Socrates Mesiona has called for urgent action to address the historical displacement of indigenous communities in southern Palawan, denouncing the continued denial of land rights to the Molbog and Cagayanen peoples.

In a virtual session of the Catholic Educational Association of the Philippines (CEAP) on Wednesday, the Apostolic Vicar of Puerto Princesa underscored the unresolved injustices committed during the Marcos-era land seizures on Bugsuk Island, where more than 10,000 hectares of ancestral land were taken from the Molbog people for tourism development.

“Justice, and only justice, you shall pursue,” Mesiona said, quoting Deuteronomy 16:20. “As people of faith, we are called to defend the rights of the marginalized and oppressed.”

The bishop said new attempts to displace the same communities persist, citing renewed eviction threats last year in the area of Maria Hangin—again tied to tourism expansion. He described these efforts as part of a larger pattern of systemic marginalization.

Mesiona revisited events that began under Martial Law in the 1970s, when the Molbog community was forcibly displaced from more than 10,000 hectares of land on Bugsuk Island, allegedly for a tourism project. The bishop underscored how that loss of land was never redressed, leaving scars that are still felt today.

In the sitio of Maria Hangin, the same community resisted eviction during the same period. That resistance, Mesiona noted, is once again being tested—citing a renewed threat of eviction just last year for yet another tourism-related development.

“These are not just stories of land,” he said. “These are stories of dignity, identity, and survival.”

More than 120 representatives from Catholic schools attended the session, which also featured speakers from the Sambilog Balik-Bugsuk Movement and PAKISAMA. Mesiona called on the Church to stand in solidarity with the Molbog and Cagayanen by supporting the recognition of ancestral domain rights and pushing for reparation.

“True independence means justice that reaches even the farthest islands,” he said.

Over 76 days, the community has rotated shifts, cooking in communal pots, organizing nighttime patrols, and sharing plastic mats under bamboo shelters. The rainy season has begun, and nights are colder. Yet families still lie awake under sheets of tarpaulin, listening for any signs of movement in the dark.

Children, too, are part of this vigilance. While others their age are in classrooms or playgrounds, some Marihangin youth now help scan the perimeter, passing flashlights and keeping logs of any suspicious activity. What began as a defense by elders has become an intergenerational act of resistance.

Despite their constant presence and repeated appeals, no national agency has visited the sitio to intervene or offer assistance. The community remains in limbo—caught between a slow-moving bureaucracy and the imminent threat of land seizure.